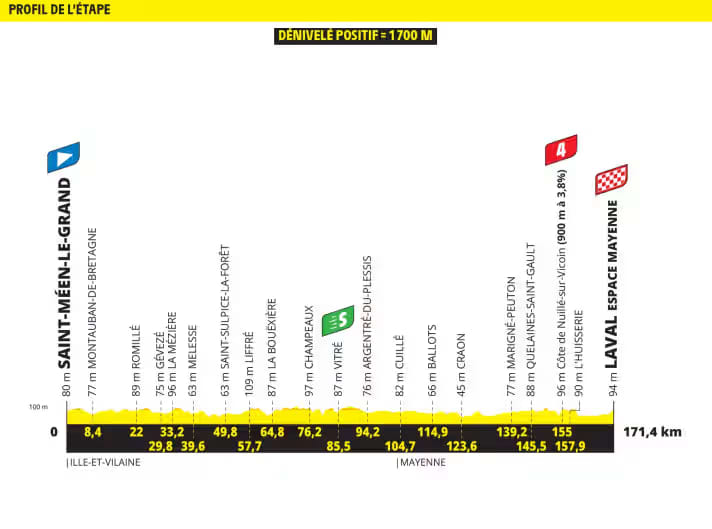

Tour de France 2025 - Stage 8: Saint-Meen-le-Grand - Laval Espace Mayenne | 171,4 Kilometers

After the classic stages, the Tour is likely to enter calmer waters. The provisional classification is set, everyone has found their role, which suggests a quiet eighth stage that will probably end in a bunch sprint.

There are no significant topographical obstacles to overcome, with the elevation gain spread over many small hills. The approach to the finish in Laval includes the typical French road obstacles: at 3,000 meters, the peloton circles a roundabout for a U-turn. Two more roundabouts are passed through straight ahead.

The home straight is 1.5 km long, 6.5 meters wide, and climbs 27 meters over the last 1,000 meters. 200 meters before the finish, the road makes a slight left turn, so you need to be at the front here to have a chance in the sprint.

The field of sprinters has already thinned out somewhat. Nevertheless, there are numerous candidates for the sprint. The favorites are presumably Jonathan Milan, Tim Merlier, and Biniam Girmay. Perhaps Phil Bauhaus or Pascal Ackermann will manage a surprise.

Due to the curve shortly before the finish, we simulate a sprint over 200 meters on the slightly ascending home stretch.

The number of the day: 0.14 seconds

In the final sprint on Boulevard Pierre Elaine, the most aerodynamic bikes once again prevail. In our simulation, the Cervélo S5 is tied with the Van Rysel RCR-F Pro. Van Rysel's top aerodynamics and the lower weight of the S5 neutralize each other on the slightly uphill finish straight, and they are mathematically tied.

With a lightweight bike that no sprinter would use, the gap at the finish line would be 0.14 seconds. In addition to bike aerodynamics, how low the rider ducks over the bike is also very important in the sprint. Mark Cavendish was the first sprinter to perfect his sprint in this regard and train specifically to bring his power to the road in the most aerodynamic position possible.

We saw what a difference this can make on the third stage. Tim Merlier won by a tire width against Jonathan Milan, who was initially in the lead. Merlier ducked visibly lower over his bike than his Italian rival, who presumably generated more power.

The (almost) complete field in the 200-meter final sprint of the eighth stage*

The table shows: In the sprint, the aero bolides are among themselves. Weight plays only a minor role on the slightly uphill finishing straight.

*) The calculations are based on the bikes tested by TOUR in the laboratory and wind tunnel. The machines used in the Tour de France may differ in detail. Of course, we were not yet able to examine last-minute prototypes. Background information on the simulation.

Our expert

Robert Kühnen studied mechanical engineering, writes for TOUR about technology and training topics and develops testing methods. Robert has been refining the simulation calculations for years, they are also used by professional teams.