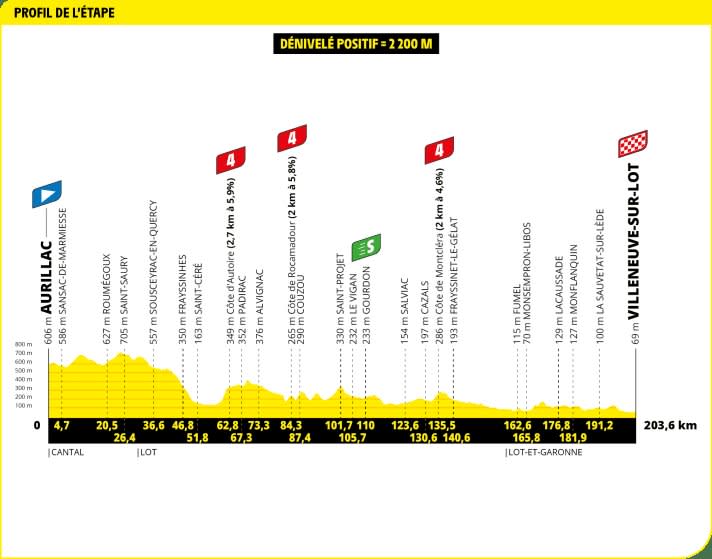

Tour de France 2024 - Stage 12: Aurillac - Villeneuve-sur-Lot | 203,6 Kilometers

On paper, the twelfth stage does not present any major difficulties. There are 2,200 meters of altitude to overcome over 204 kilometers. The start is still a little mountainous, but the stage flattens out towards the end. How the race develops has a lot to do with the previous day and the motivation of the riders. The day before was very hard, sprinters may have finished on the last groove.

In principle, there can be both: a bunch sprint or a successful breakaway. If a good group goes early, even before the first mountain classification of the fourth category, it is conceivable that they will make life difficult for the sprinter teams. With the right composition, such breakaway groups have in the past pulled out such big leads in the second half of the Tour that the sprinters’ teams were no longer able to catch up. The rule of thumb is: one minute per 10 kilometers is considered catchable (for example 47 vs. 43 km/h). In the last ten to 20 kilometers, two minutes per 10 kilometers is also possible if the breakaway is flat and the sprinters’ peloton takes it seriously and rides at an average of 55 km/h or more (and the escape group “only” manages 46 km/h).

One argument against the breakaway is that several sprinter teams have come away empty-handed so far and this is the third last opportunity to change that. The cohesion in the sprinters’ team is always a given, the breakaway only works well if the constellation is right. This means that no one who is still within striking distance in the overall classification can be part of the group. A strong sprinter is also poison for an escape group. Ideally, several similarly strong riders should have a realistic chance of finishing the breakaway victoriously.

In our simulation, we assume that the action begins shortly after the start and that a large group is formed early on. What influence would the material have on an escape over 175 kilometers?

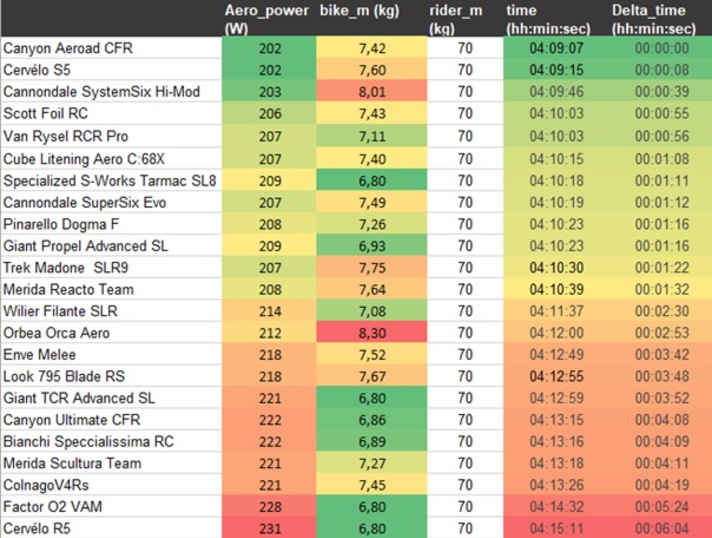

Number of the day: 6:04 minutes

The fastest aero bike saves 6:04 minutes mathematically over the 175 kilometers of escape that we simulate, compared to the slowest bike in the field.

The bike therefore plays a part in making a successful escape. But the composition of the group, an efficient riding style and good pacing are essential. The escapees should keep a reserve after the stormy initial phase in order to be able to hold their own against the pressing peloton in the finale. Then the sprinter teams could miscalculate.

The (almost) entire field at a glance*

*) The calculations are based on the bikes tested by TOUR in the laboratory and wind tunnel. The bikes at the Tour de France may differ in some details. Of course, we have also not yet been able to examine last-minute prototypes. Background to the simulation.

No surprise: good escape bikes are aero bikes. After all, an escape is basically a time trial.

Review: World champion sprint extended

Aero bikes are also used in the sprint: On Tuesday, Mathieu van der Poel and his Alpecin-Deceuninck team managed the perfect lead-out, world champion-like, so to speak, to match the jersey. With 1400 meters to go, the Alpecin-Deceuninck team was in the lead with four men and formed the front of the racing peloton. Christophe Laporte from Visma | Lease a Bike battled alongside Wout van Aert as the lone rider. Alpecin held on to the lead through the combination of corners, van Aert lost contact with Laporte and van der Poel opened his lead-out sprint just before the 400-meter mark, accelerating to full sprint speed and giving Jasper Philipsen a perfect launch pad. The latter extended the sprint and was able to hold on safely by a wheel’s length. The riders behind caught up, but were unable to completely make up for their positional disadvantage. The first really orderly sprint move in this Tour brought an equally clear result and shows that the lead-out method still works when it is implemented as well as it was on stage 10.

Our expert

Robert Kühnen studied mechanical engineering, writes for TOUR about technology and training topics and develops testing methods. Robert has been refining the simulation calculations for years, they are also used by professional teams.