Tour de France 2024: TOUR Tech briefing for Stage 14 - which bike is the fastest on Pla d’Adet?

Robert Kühnen

· 13.07.2024

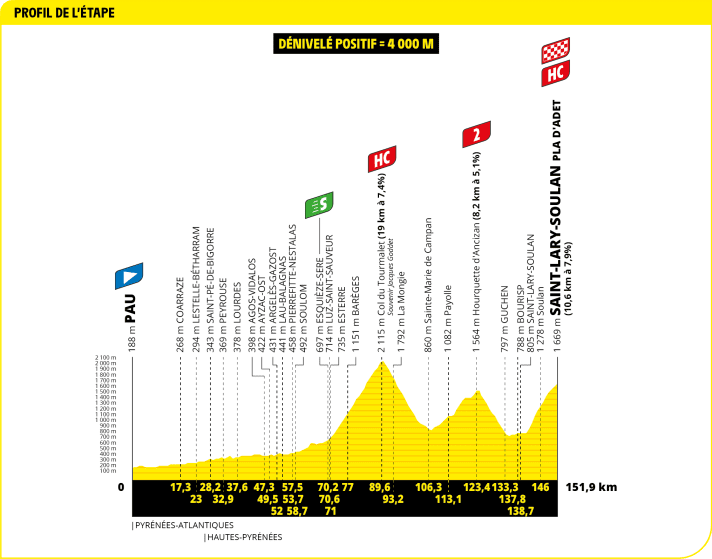

Tour de France 2024 - Stage 14: Pau - Saint-Lary-Soulan Pla d’Adet | 151.9 Kilometers

Off into the mountains: 4,000 meters of altitude to climb on the first stage in the Pyrenees. First in the profile is the majestic Tourmalet, a mountain of the highest category, followed by a second category climb and finally the difficult final climb, which is very steep right at the start with gradients of over 10 percent. The final climb has an average gradient of 7.9% over 10.6 kilometers.

What course will the stage take? Will Pogacar attack again? And if so, where? Will he repeat the Galibier tactic and attack on the Tourmalet, which is the steepest towards the end? Or will he now ride more defensively after Vingegaard looked so strong in the Massif Central and so effectively neutralized Pogacar’s lead on stage 11 at the rather inconspicuous Col de Pertus?

There is much to suggest that Pogacar will act more cautiously. The two superstars will probably eye each other and wait for a sign of weakness from the other. It is quite possible that they will neutralize each other completely, as the final climb is not very suitable for a late attack, as the gradient eases towards the end.

But even if the superstars only neutralize each other, breakaways could fall victim to the hellish pace of the two when they contest their elimination race over three summits and sprint for another stage win at the end.

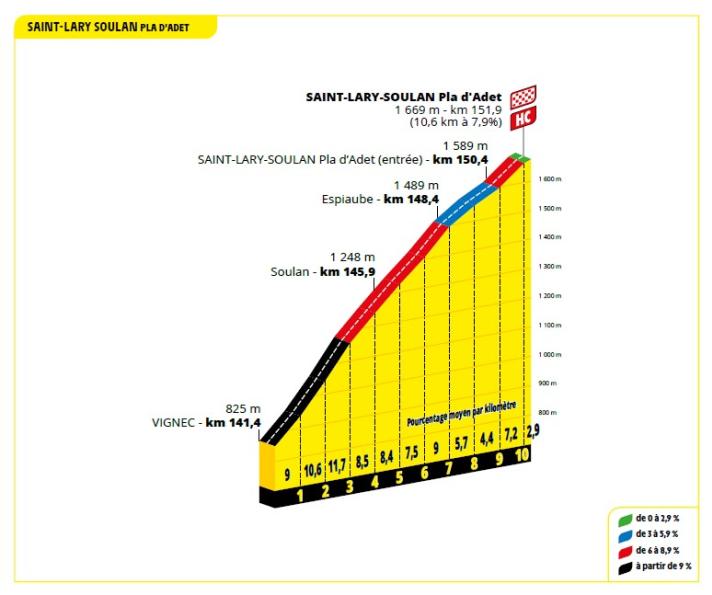

Our simulation revolves around the final climb. Who has the best material in the battle for yellow and/or the stage win when the final climb is taken at full gallop from bottom to top?

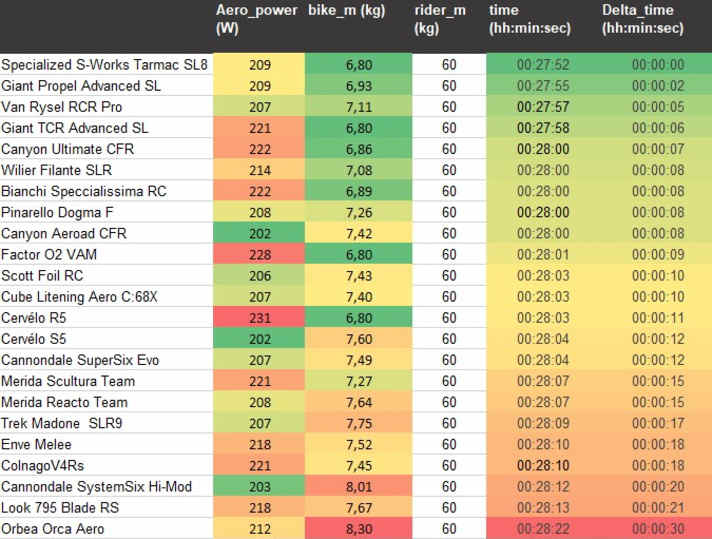

Number of the day: 30 seconds

According to our simulation, the fastest bike has an advantage of 30 seconds over the slowest on the final climb. Realistically, however, nobody who wants to have a say in this stage will be riding an 8.3 kg bike, which comes last in our calculation. On the other hand, even the favorite is on a not very fast bike, as the table below shows. We weren’t allowed to weigh Pogacar's bike this year, but the 7.45 kg in our list is the weighed weight from last year and the specs haven’t changed. Any differences in weight could only be explained by a lighter frameset. However, the fact that we weren’t allowed to weigh it suggests that the bike is still overweight. That, in turn, is actually astonishing: the best rider in the world’s most important cycling race rides a bike that does not make full use of the regulations. That is difficult to understand.

We have an analytical answer to Jonas Vingegaard’s daily S5 or R5 oracle: the R5 is actually one second faster on the simulated final climb. Unless Vingegaard opts for a 1x12 gearing like on the Galibier. With 300 grams less mass and even better aerodynamics, the S5 would be a few seconds faster than the R5 in this set-up.

The (almost) entire field at a glance*

*) The calculations are based on the bikes tested by TOUR in the laboratory and wind tunnel. The bikes at the Tour de France may differ in some details. Of course, we have also not yet been able to examine last-minute prototypes. Background to the simulation.

Table: The virtual riding times on the final climb. As expected, the lightweight bikes are at the top of the rankings. There are aerodynamic effects on the flatter part of the climb, which is why the Tarmac SL8 takes first place in the overall ranking with a good compromise between weight and aerodynamics.

Our expert

Robert Kühnen studied mechanical engineering, writes for TOUR about technology and training topics and develops testing methods. Robert has been refining the simulation calculations for years, they are also used by professional teams.