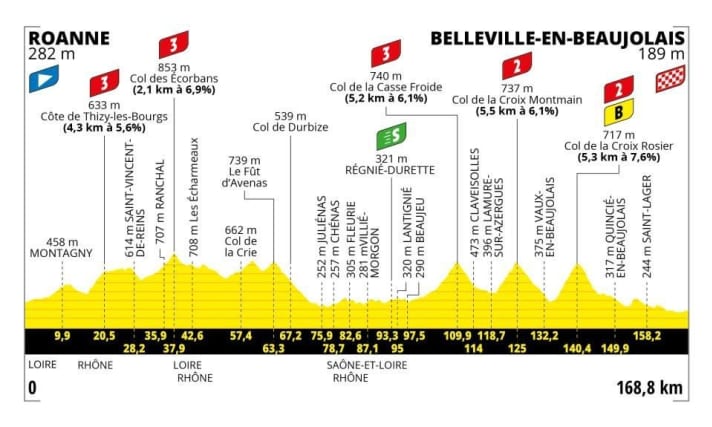

Tour de France 2023 - Stage 12: Roanne - Belleville-en-Beaujolais | 168,8 Kilometres

The twelfth stage of the Tour de France 2023 is breakaway terrain. Especially the second half with three similar climbs - all around 5 km long with 6-7.6% average gradient - is made for climbers and tempo-resistant soloists. The final 28 km are mostly downhill. A downhill rider with time trial skills could break away from a group here on his own, but it could also come to a sprint of a group as on the tenth stage. In the overall classification, a change is not very likely, especially in view of the upcoming mountain stages. Attacks are still possible, of course, if the peloton gets tattered and the race becomes confusing. Something can always happen in the Tour de France. If you’re in yellow, you have to watch out like a lynx. As always, we ask the question: Which equipment would be the right one to attack from a breakaway group?

Tour de France 2023: Our simulation for stage 12

For this we simulate an attack two kilometres before the summit of the Col de la Casse Froide, 60.9 kilometers from the finish. The attack starts with a sharp acceleration. As a result, we let the virtual breakaway race toward the finish with an average of 352 watts. We simulate the natural behavior: our rider invests more power uphill than downhill. Under these conditions, he achieves an average of 43.4 km/h.

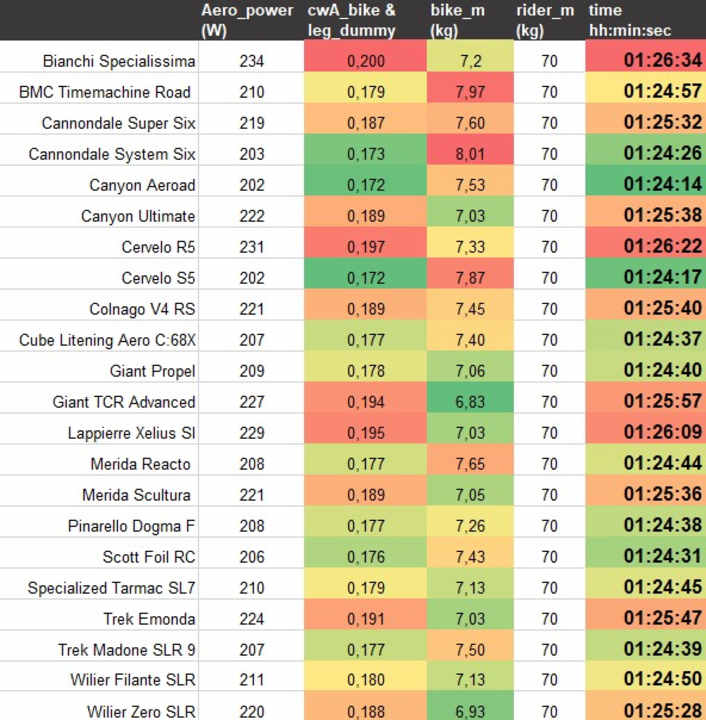

Number of the day: 2:20 minutes

2 minutes and 20 seconds faster is the fastest bike of the day than the slowest in our list. Canyon Aeroad once again leads the standings on the twelfth stage of the Tour de France 2023. Unless Jumbo-Visma chains 1x12 again, then the Cervelo S5 beats the Canyon mathematically by 12 seconds.

Should a group arrive at the finish together, the aero bikes would also be a good choice. Until two kilometres before the finish it goes downhill. There are 15 meters of elevation gain from 2,000 meters to the red devil’s lap, the last 1,000 meters are nearly flat, and the finish is two meters lower than the 1,000-meter mark - that's even more clearly aero terrain than the undulating road there.

Around 400 meters before the finish, a sharp right-hand bend is the last obstacle before the finish line.

The (almost) complete field at a glance (60-km-solo)

*) The calculations are based on the bikes tested by TOUR in the laboratory and wind tunnel. The bikes at the Tour de France may differ in details. Of course, we have not yet been able to examine last-minute prototypes either.

Our Expert

Robert Kühnen studied mechanical engineering, writes for TOUR about technology and training topics and develops testing methods. Robert has been refining the simulation calculations for years, they are also used by professional teams.