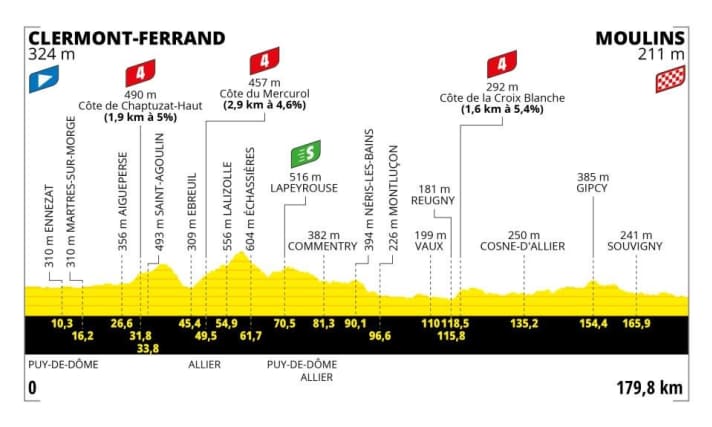

Tour de France 2023 - Stage 11: Clermont-Ferrand - Moulins | 179,8 Kilometres

The eleventh stage of the 2023 Tour de France is a sprint stage on paper. The topographical difficulties are manageable, the finale is flat. Until next Thursday, it is also the only opportunity for sprinters to make a positive impression. But in the Tour de France, anything is possible. A well-staffed escape group could also get through. The question is who will muster the greater motivation.

The fastest stage in this years Tour de France so far was the eighth, with an average of 47.8 km/h. That’s pretty damn fast. Can a group even hold its own when the whole peloton is chasing at hellish speeds? If everyone is chasing, then no, the balance of power is clearly in favor of the peloton. Those who are hiding well here hardly feel any wind resistance and therefore save an enormous amount of energy and could ride fresh to the front at any time. But everyone is never chasing. Most of the time, two or three sprinter teams share the job, but they only leave two riders because they want to save the firepower for the finale. Effectively, therefore, there are not many more riders in the chase than there are in the front. So the question is: who is more motivated and who has better timing?

Tour de France 2023 - stage 11: Which sprinters could fight for the win?

Which teams might be motivated to force a bunch sprint? Caleb Ewan, Dylan Groenewegen and Biniam Girmay have yet to score a win, so their teams are motivated accordingly. Fabio Jakobsen may have recovered from his injuries, so Soudal - Quick Step is pulling in for him. Wout van Aert is also desperate to win, but will Jumbo-Visma ride full on stage 11 of the Tour de France 2023, for a flat final that doesn’t suit van Aert ideally? Alpecin-Deceuninck has green and wants to extend its lead, but also has three stage wins under its belt. They’re not guaranteed to go first. Mark Cavendish is out of the Tour de France, leaving Astana weakened. Mads Pedersen won his stage - and a very flat finale doesn’t suit him either.

We can see that the chances for a group might not be that bad, because the motivation of the best sprinters’ teams is not that clear and the peloton is already tired in the middle of the Tour de France. But this is a tech briefing. So let’s move on to the technology. Readers of this newsletter already know the fastest bikes of the day by heart, because they are always the same.

Number of the day: a hundredth of a second

But on stage 11 of the Tour de France 2023 we expect a tuning trick: Jumbo-Visma will probably mount 1x12 gears again due to the profile, making Wout van Aert’s Cervelo S5 potentially the fastest bike by a hundredth of a second in a 150-meter sprint. Of the 202 watts we determined in the wind tunnel, about three watts go down for the bike without a front derailleur with a closed aero chainring. We have adjusted the value in the list below accordingly.

But the fastest bike is of no use if the situation is different. Suppose a scenario like the eighth stage develops and a group leaves early but is bigger and better manned. What would the riders in the group have to do to keep the peloton at bay in the long run? And how quickly can the peloton catch up with breakaways, how big does the time cushion have to be?

The breakaway can go 50 km/h, but only the peloton can go 60 km/h

With a good position and good equipment, a pro with 380 watts can ride at around 49 km/h - on the flat. That’s about the same as the threshold power of a normal pro. In a four-man breakaway group, a 50 km/h pace can easily be maintained for four hours, i.e. for about 200 km, because 100-130 watts can be saved in the slipstream. For a while, breakaways can also increase the pace to around 52 km/h. Above that, it’s difficult to keep it up for longer with a few competitors, because the air resistance is too strong.

The peloton, on the other hand, can go up to 60 km/h - all other things being equal, this requires 670 watts of pedaling power at the top. This is possible if the riders at the front rotate and are only in the wind for a relatively short time. This is especially successful when many join in, i.e. rather at the end of a stage of the Tour de France when the position battles begin. The speed difference between escapees and an unleashed peloton is then around 8 km/h. This means that the peloton can make up about one and a half minutes per 10 km with maximum collective effort - if the escapees offer maximum resistance.

The (almost) complete field at a glance (150-meter sprint)

*) The calculations are based on the bikes tested by TOUR in the laboratory and wind tunnel. The bikes at the Tour de France may differ in details. Of course, we have not yet been able to examine last-minute prototypes either.

Our Expert

Robert Kühnen studied mechanical engineering, writes for TOUR about technology and training topics and develops testing methods. Robert has been refining the simulation calculations for years, they are also used by professional teams.