Tour de France 2023 - Stage 13: Chatillon-sur-Chalaronne - Grand Colombier | 137,8 Kilometres

The first of three mountain stages in a row at the Tour de France 2023 consists of a 120-kilometer run-up, spiced with a moderate climb and a big chunk at the end: 17.4 kilometres with an average of 7,1 percent lead to the finish on the Grand Colombier.

Slipstream is important on Grand Colombier

On paper, the staircase-like climb isn’t super hard; slipstreaming is an issue here. But there are steep sections with 12 percent in the first and second sections. The GC riders will rush into the climb relatively fresh, which argues against early attacks. They’ll probably test themselves and only really attack when a weakness is apparent on stage 13 of the Tour de France 2023.

If that keeps the duel between Vingegaard and Pogacar cold, it will come down to a late attack, which is more Pogacar’s specialty. He doesn’t have to worry about his bike, he always rides the same setup, which our reporters Jens Klötzer and Julian Schultz had on the hook of their scales: 7.42 kg are set for the Colnago V4 RS.

Tour de France 2023: Which bike will Vingegaard ride on stage 13?

Jonas Vingegaard has two machines and many wheels to choose from and, given the final climb, will probably prefer his Cervelo R5 to the S5. According to our calculation, however, the S5 would be minimally faster - whether you look at the mountain as a whole or just the final.

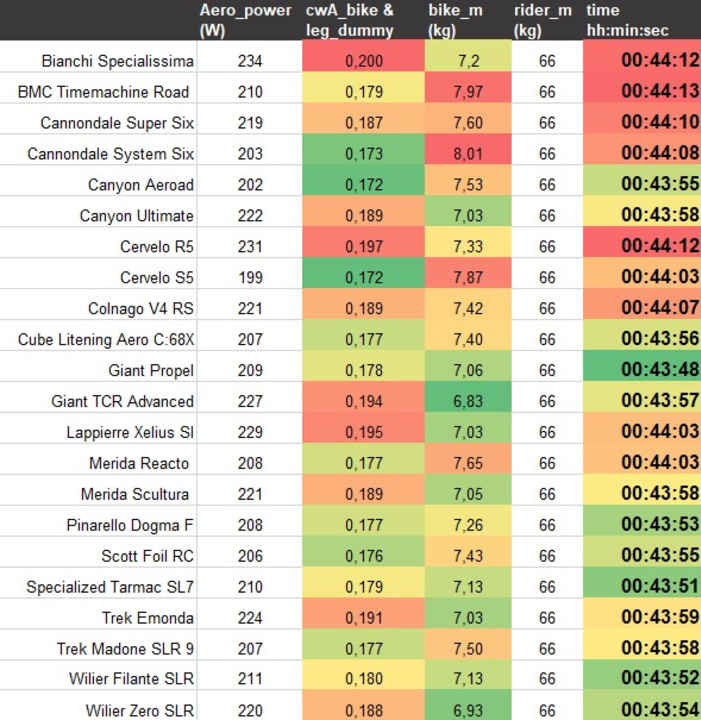

Running parallel to the GC riders’ race will likely be a race of breakaways for the win on stage 13 of the Tour de France 2023, should their advantage be enough to do so. Our simulation of the day includes the entire final climb. Which team would have the fastest bike for a climber on the run?

Number of the day: 25 seconds

The fastest bike for breakaways climbing the final climb evenly (6.2 W/kg), 25 seconds in front of the slowest bike, is the Giant Propel - a good compromise of light weight and good aerodynamics. The even lighter TCR model, which meets the UCI weight limit - also according to our on-site observations - would be slower.

The (almost) complete field on the final climb

*) The calculations are based on the bikes tested by TOUR in the laboratory and wind tunnel. The bikes at the Tour de France may differ in details. Of course, we have not yet been able to examine last-minute prototypes either.

Our Expert

Robert Kühnen studied mechanical engineering, writes for TOUR about technology and training topics and develops testing methods. Robert has been refining the simulation calculations for years, they are also used by professional teams.

- TOUR Tech briefing stage 12

- TOUR Tech briefing stage 11

- TOUR Tech briefing stage 10

- TOUR Tech briefing stage 9

- TOUR Tech briefing stage 8

- TOUR Tech briefing stage 7

- TOUR Tech briefing stage 6

- TOUR Tech briefing stage 5

- TOUR Tech briefing stage 4

- TOUR Tech briefing stage 3

- TOUR Tech briefing stage 2

- TOUR Tech briefing stage 1